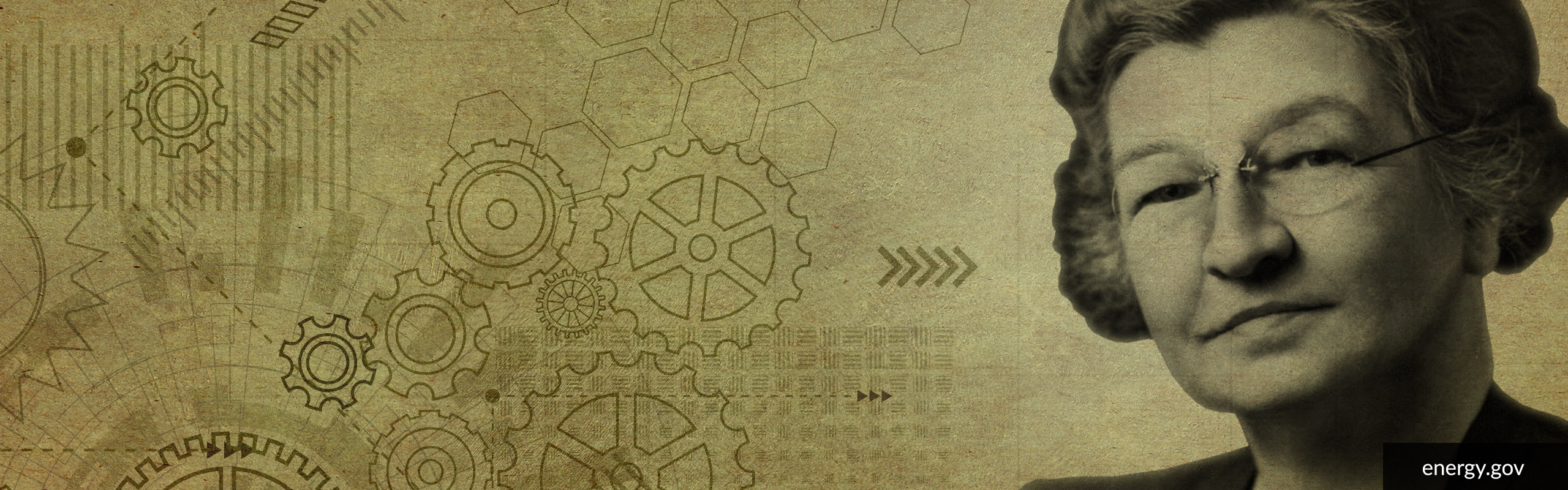

On 10 February 1883, Edith Clarke was born. She was one of the nine kids of John Clark, a lawyer from Maryland. Since she was twelve, after the death of her parents, she was further raised by her older sister. For this reason, she was the one who had to take care of her own future. Edith, an ambitious individualist, decided to make use of her inheritance and invest it in education. She enrolled in the Vassar College, where mathematics and astronomy piqued her interest the most, and then she continued her studies in San Francisco. She began to study civil engineering but dropped out to work at AT&T. Interestingly, she was involved in a project of creating the first transatlantic connection which we have already talked about many times. From today’s point of view, it might seem funny, considering the widespread access to spreadsheets and specialised software, but Edith Clarke was like a “human computer” at AT&T, and she conducted all those calculations that were needed by the engineers who worked on the solutions that were to connect America and Europe. However, this was not the end of Edith Clarke’s ambitions, which can be evidenced by the fact that beside professional work, she continued electrical engineering studies at Columbia University. A few years later, she was admitted to study this subject at the prestigious MIT, to finally get her M.Sc. there. But most importantly, she was the first woman who managed to do that.

It turned out, though, that her impressive knowledge certified with a diploma was not enough to compete successfully in a “male-dominated profession,” and Clarke could not get a job as an engineer. Employment with GE, where she supervised calculation works, was just a partial success. Clarke had her own approach to work – she invented one of the first graphing calculators, which not only solved line equations involving hyperbolic functions of electric current, voltage and impedance, but also did it much faster than the methods used back then. This is even more important as the speeding process of electrification and the growing need for electrical energy pressured network operators to work intensely on bettering the power transfer. Clarke filed a patent in 1921 (granted in 1925), and just a year later GE offered her the dream engineering job. Thanks to that, she went down in history as the first female electrical engineer in the US. She was also the first female speaker (and member) in history to present her analyses during a meeting of the American institute of Electrical Engineers. Her analytic skills also contributed to the building of the Hoover Dam, which for many years was the biggest hydroelectric power plant in the world.

An important part of Edith Clarke’s heritage is her didactic work and related achievements – she wrote a two-volume textbook on research methods and the improvement of the effectiveness of the electric power systems and the efficiency of electronic devices. Moreover, Clarke taught at the University in Austin for over 10 years; and there, she became a Professor of electrical engineering. Once again – as the first woman in the United States.

As we have already mentioned, today it is hard to imagine a device that… cannot count. Complicated mathematical operations in real time are performed by measuring devices, such as oscilloscopes or multimeters, industrial sensors and transducers or microprocessors, but also the simplest integrated circuits, which are used in consumer devices or even toys. For this reason, the achievements of Edith Clarke might seem like ancient history, even though they are less than a 100 years old. A similar thing happened with the quality of energy. Modern power supplies, using the electricity from highly stable grids, equipped with precision converters, offer output voltage that falls within a range of few microvolts. Today, every automated production facility carefully monitors the quality of electrical energy. The challenges faced by Edith Clarke are long forgotten now. But are they all really gone? Well, definitely those related to electricity…